Just over a year ago, I was just home from trip to Gros Morne National Park in Newfoundland and was researching my next Canadian adventure when I came across the West Coast Trail in British Columbia. Admittedly I had not heard of it before which perhaps is evidence of Canadians’ general disregard or ignorance of their own country’s treasures.

The 75 km WCT trail is known to most as having its origins as a life saving route for the many shipwrecks that once occurred in the turbulent currents of the Juan de Fuca Strait (affectionately known as the Graveyard of the Pacific). A number of high-profile shipwrecks, including the Valencia in 1906 (125 people drowned), embarassed the federal government of the day to do something. Lighthouses linked by a trail were constructed as well as a handful of rescue shelters stocked with provisions that would allow survivors to stay alive until help arrived. The Dominion Lifesaving Trail, as it came to be known in 1907, was primitive by any standard given the harsh geography and wet climate.

The origins of the trail go much farther back, in fact. A trail through the area has existed for hundreds of years, connecting a number of First Nations communities including the Huuay-aht, Ditidaht and Pacheedaht. Small Native communities continue to exist to this day though their main transportation routes are by way of remote logging roads or by water.

The WCT forms part of the Pacific Rim National Park. It is a coastal trail which is to say you are not climbing mountains. But you are navigating through harsh terrain, rainforest and in some cases tide waters to arrive at the other end. I chose to access the trail from the north end (Bamfield) having heard that the most challenging stretch is in the south (toward Gordon River). This would give me a chance to burn through food and hence lighten my backpack before the heaviest part of the journey. When you’re carrying 60 lbs on your back, this was a key consideration for me.

I arrived Sept 3 in Bamfield after a bone-jarring hours-long jaunt down a remote, washboarded logging road from Port Alberni. I arrived in time to do the mandatory Parks Canada briefing on “How not to become bear fodder or drown yourself in the tides.” I spent the night in the local campground at Pachena Beach, spending the evening double checking my provisions and contemplating the start of my trek the next morning.

Incidentally, before I left for the west coast, many friends worried about my decision to do this trek alone. I had made the offer to a couple of people when I first began planning the trip but I got no takers. So what’s a girl to do? I also knew the trail would by well travelled and that the campsites along the way would be busy. As I suspected might happen, I met some people on the shuttle bus to Bamfield with whom I ended up tagging along for almost the entire trip.

Rather than bore you with a daily diary of 6 days, what follows below are some highlights with photos. The photos captured on my phone do not do justice to the wildness and serenity of this part of the world.

The Trail

At 75 km, the trail meanders through all kinds of topography and conditions. Parks Canada has built extensive infrastructure to assist hikers in the form of footbridges, boardwalks, manual cable cars and ladders. Wood structures, even those made of cedar, survive 15-20 years in the rainforest at most (unless a giant tree falls in a storm, in which case whole sections of boardwalk or ladder can be obliterated immediately), so maintenance is an ongoing battle. Most of the trail however is just dirt track, often mired in goopy mud pits or laced with tricky tree roots. Some sections, you have your choice of an interior land trail or a beach walk. But before you get dreamy-eyed about “a walk on the beach” keep in mind the beaches vary from loose sand to shifting gravel to large boulders, none of which is conducive to heavy backpacking. You also need to know the high and low tide times or else risk finding yourself drowned and washed up in Japan. One day of my trek was spent walking almost entirely on the beach – 10 km of shifting sand and gravel or tiptoeing over slippery granite. Wheee!

Not all of the trail is designed to kill or maim you thankfully. A dozen or so bridges allow for easy crossing over steep canyons. Hand operated cable cars offer a fun and clever way for hikers to get across deep rivers. Ladders (over 100 of them) help hikers avoid annoying switchbacks. One of the ladders was well over 20 metres high. Boardwalks negotiate some of the muddy terrain and vary in condition from immaculate and speedy to rotten and death-trappy. In two places, you must take a boat to cross a significant body of water (at Nitinat Narrows in the middle and at Gordon River in the far south).

Wildlife

After all the hype during the Parks Canada briefing about bears, I didn’t see any. Not. One. I also didn’t see any cougars or wolves, for which the region is known. I saw enough bear shit to fertilize the Prairies, however, so they were definitely around, using the trail as their loo.

That said, on my first day I saw a whole colony of noisy sealions sunning themselves on a rocky promontory. Wow, what a racket! And later that day, while relaxing at my oceanview campsite, I watched as a humpback whales did their ritual feeding dance so close to the shore – blowhole blast, hump, hump, flash of the tail. Repeat. It went on for hours.

I also saw a pod of Orcas near the Carmanah lighthouse on my 4th day. I saw a number of bald eagles and some seals. All in all, I’m happy I got to see swimmy mammals and flighty tweety birds than bitey growly predators.

Living Large

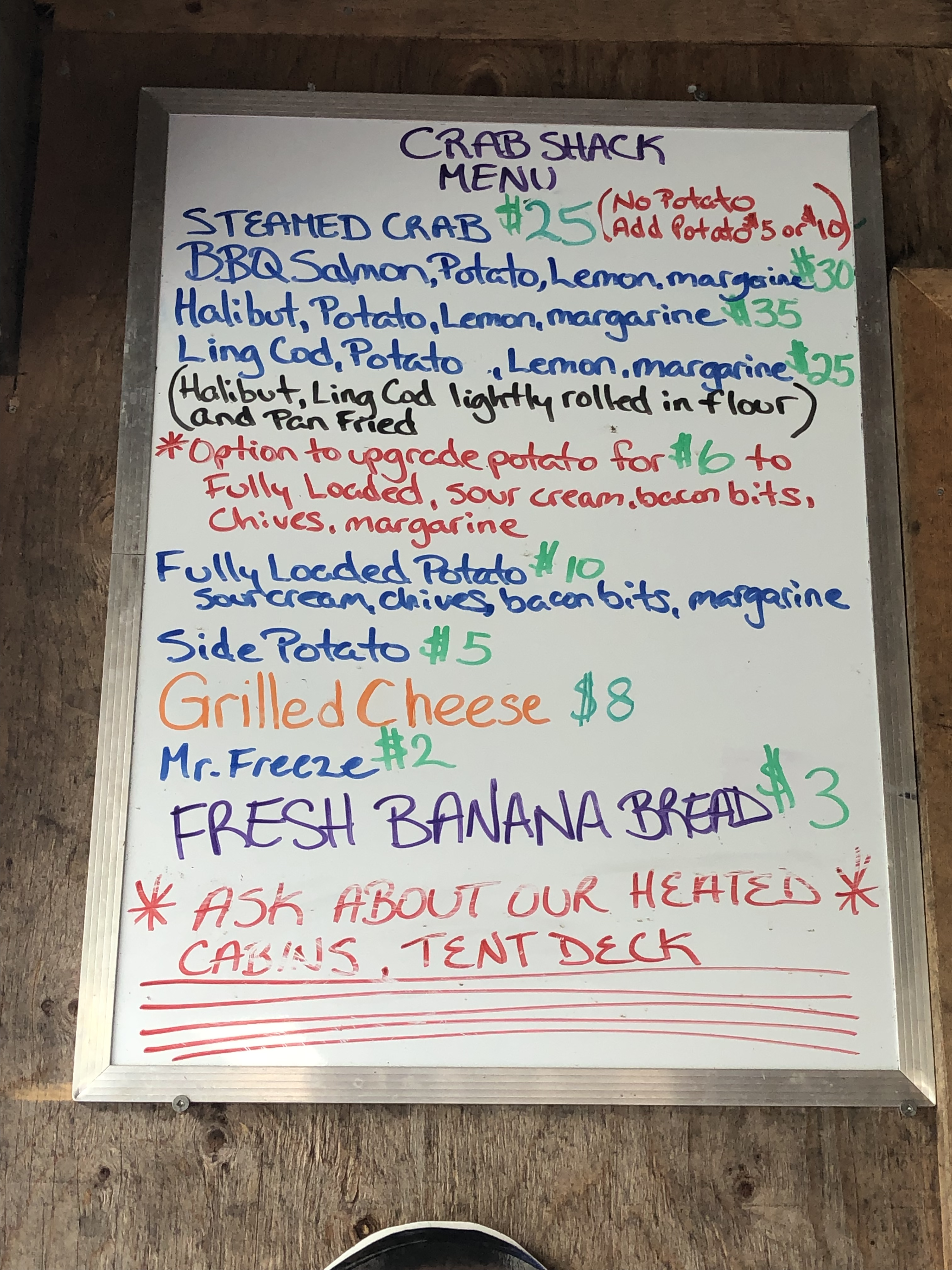

Like a mirage on a desert horizon, the crab shack at Nitinat Narrows is an unbelievable luxury in a hostile environment. The little floating restaurant is operated by the same First Nation that is contracted by Parks Canada to provide the water taxi service at the narrows. The small wood structure is a great respite from the chill and the wet, equipped with a wood burning stove and plenty of covered seating. They even have small rooms to rent out for those who really want a break from the grind. Prices are on the steep side, considering all the seafood is caught on site. But given that the place operates only during the short season the WCT is open and that everything besides seafood needs to be shipped in from a community miles away, the prices are understandable. I had the salmon and it was de-lish. The meal was the highlight on a day that saw us trek 17 km, the longest walk of the 6 days.

Campsites

There is nothing preventing you from camping wherever you like along the trail, but the denseness of the bush and picture perfect settings of the beach campsites makes the latter a better option. Add to that the campsites have bio toilets (non flush but relatively clean), sources of fresh water and lots of driftwood for fires – about as Hilton as you can expect.

Darling River was the only one I stayed at that had a good number of sites under forest cover. The rest were pretty much all beach based (i.e. setting your tent up on sand). Tsusiat was stunning with its adjacent waterfall. The day we arrived the beach was bathed in cloudless sunshine. Cribs Creek was nice but mostly memorable as the restful terminus of a 17km day. Walbram River was awash in freshly cut cedar firewood courtesy of the nearby trail maintenance crew. All the hikers congregated that night for a communal campfire and were awestruck by the glorious sunset. The only downside was the rain that began before dawn the next morning, making for a heavy, wet tent to pack up. Our last campsite was Camper’s Creek, a non-descript place almost completely absent of firewood. Every one of these campsites sites was nestled between the foreboding darkness of a towering rainforest and the relentless crash of the ocean surf.

Odd things on the trail

Offshore from the trail is a graveyard of sunken ships, none of which are visible today. There are some cool relics of past logging activities and even an old motorcycle that we came across our first day.

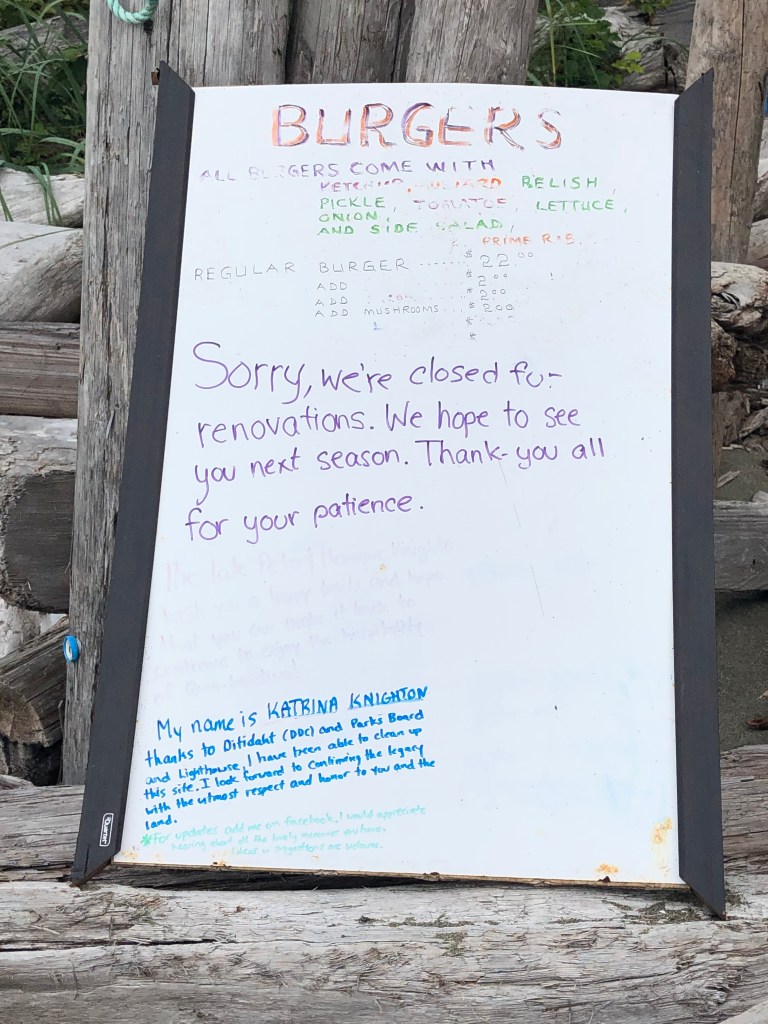

Chez Monique was a burger restaurant along the trail operated on First Nations land. The owner, Monique passed away last year and there had been some controversy over the restaurant’s continued operation. The controversy ended when winter storms severely damaged the building with driftwood.

The physical challenge

Unless you’re someone who regularly pushes the physical limits of your body, this or any other wilderness trek will kick your ass. Fortunately, I got off fairly unscathed overall. My one mistake was packing too much. I overestimated significantly how much I would eat and how long the trek would take. I assumed 8 days but probably had enough food for 10. It only took me 6. I had no idea how much my backpack weighed until I got to the restaurant at Nitinat Narrows (day 3!) where they had a scale. For fun my 3 hiking mates and I weighed our packs. Theirs were each around 45-50 lbs. Mine was 60. Ideally your pack is 25% of your bodyweight. 33% is the maximum. Mine was 40% of my bodyweight. This was nearly debilitating for the first two days of the trek until my body aclimatized. The weight decreased somewhat as I ate through my foodstores but was quickly restored after the rain at Walbram left me with a soaking wet tent to carry.

Apart from a foot blister, which I kept under control by treating quickly, the main annoyance was aching hips from the heavy pack. I finished the trail on Monday and spent almost all of Tuesday in my Victoria hotel room not moving.

Epilogue

In a modern world, we rarely get to experience the world for its untouched beauty. Asphalt, concrete, ubiquitous shelter, easy access to potable water, cell phones and central heating buffer us from elements such that most Canadians from urban areas never experience the power of nature. I thought of this often on my walk and the importance of getting young people interested in the wilderness of their country, a feature that is vanishing quickly elsewhere in the world with startling pace and permanence.

I want to conclude by thanking the three lovely Calgarians who I befriended at the start of the trip – Brenda, Peter and Bruce. All three are extremely experienced backcountry hikers and it was most reassuring to be in their presence for my own sojourn into the wild.