I have been back home now since last Tuesday night trying to revert back to my old life. It hasn’t been an easy transition, which is not surprising, and it has kept me from writing the final journal entry. Nonetheless, I thought I better get on this before the immediacy and clarity of my thoughts begin to fade. I apologize in advance for digressing into a history lesson and for the lengthy email…I won’t feel offended if you don’t have the time to read it!

The difference between Lesotho and South Africa, despite their immediate proximity to each other, is surprising. Stepping across the border is like crossing the boundary between the developed and developing world. While Lesotho resembles many of Africa’s poorest countries with its primitive villages and nomadic herdsmen, South Africa is a modern, wealthy society. This is not to say that South Africa doesn’t have poverty. Both countries have acute poverty. In Lesotho, poverty is prominent and is the result of its isolation and lack of resources. In South Africa, poverty is surprisingly widespread in rural areas and in the townships despite the fact that the country is awash in resources, particularly gold and diamonds. In South Africa, poverty is a manmade problem and is the result of political decisions. It is the result of nearly 50 years of a violent apartheid system that used the labour of the majority black population to build a sunny, happy playground for the minority white population. Today, apartheid is gone, but it will take generations for the persistent economic segregation to go away.

Anyone wishing to understand South Africa must spend time in Johannesburg, or Jo’burg as the locals call it. This city has been the driving force of the South African economy since gold was discovered in 1889. The importance of gold to the emergence of this city is reflected in the fact that it is not even located on a body of water. Not even a river runs through the city. Its haphazard layout and its farflung suburbs is reminiscent of Sudbury, Ontario where dozens of mines carve up the city into a patchwork of human settlements over many hundred square kilometres. As

such, transportation is focused entirely on its complicated road system connecting some 500 suburbs. The economic importance of Jo’burg cannot be understated, because it was the gold industry that financed the costly and mad program of apartheid.

Which brings me to the other reason why Jo’burg is so important to understanding South Africa. It was in this city where apartheid took on its most ruthless form and where the struggle against it was most passionately and violently played out. It was here that such luminaries as Nelson Mandela, Robert Sobukwe, Stephen Biko and Desmond Tutu spent their formative years under the oppression of a fanatically racist regime and became leaders in the fight against it.

For the apartheid regime, Jo’burg was its greatest resource and its most troubling concern. On one hand, the region’s gold brought tremendous wealth to the country. On the other, the mines required a large workforce that inevitably brought blacks, whites and other racial/cultural groups together. To the apartheid regime, this co-mingling of races was intolerable. Their response to this was to forcibly expel thousands of non-whites out of the cities into distant suburbs (townships) that were far enough away to preserve the purity of races but close enough to exploit non-whites for cheap labour. Stripped of their homes in the cities, non-whites were forced into menial labour and to pay as much as a quarter of their income just on transportation to and from work.

The result of this ridiculous plan was that the apartheid government created massive poverty all around its cities. Furthermore the need for jobs

attracted many black South Africans into the townships from rural areas. This inspired yet another disastrous program of the apartheid government whereby blacks who had not already moved to urban areas would be forced to stay in black homelands. Blacks were stripped of their South African citizenship and forced to take a make-believe (and not internationally recognized) citizenship of one of these nonviable homelands that were patchworks of noncontiguous land with few resources. Men could apply to leave the townships to work in the cities on 6-month contracts but would have to leave their families behind in the homelands. These various and sundry policies of the apartheid regime divided families for months or years creating many of the social and health problems that continue to plague South Africa today (similar to what the massive population migrations caused by the Depression did for Canada in the 1930s).

South Africa’s most famous township is Soweto, today a sprawling agglomeration of settlements of between 2-4 million people (no one is really sure), located about 17km from downtown Jo’burg. Created in the late 1950s, it was here where Nelson Mandela lived after being expelled from Jo’burg as a result of the government’s resettlement plan. Mandela would not live here for long, however, as we would spend most his next years in and out of prison fighting the government’s Pass Laws. In 1962, he was sentenced to life in prison and sent to live on Robben Island in Cape Town. Mandela would remain an iconic figure in Soweto during the next 30 years of incarceration, and his wife would become a very prominent leader in Soweto in his absence.

On my arrival in Jo’burg on Aug 5, I called to arrange a tour of Soweto for the next day. It may seem strange for tourists to circulate around and oggle poor people but the locals are more than happy to receive strangers and are proud of the prominent role their city played in the struggle. Besides, a visit to any township is truly an educational experience and should not be missed. The next morning, Saturday, our tour guide Mandy picked Erika and I up at our B&B and we set out for Soweto. Mandy is a Soweto native and very proud to be. Erika and I were very fortunate that too many people signed up to be on the tour that morning to all fit in the van, leaving her and I to ride with Mandy in a separate car. This gave Erika and I a chance to travel at our own pace.

Our first stop was actually in a middle-class neighbourhood in Soweto. Who would have thought? The streets were lined with single-family homes on quiet crescents. This is not typical, but Mandy wanted to show us the changing face of Soweto. Despite its violent past, now many of Soweto’s more successful residents CHOOSE to remain there.

Our next stop was what one more often associates with Soweto. It was a shantytown, not more than a couple of kilometres from the middle class neighbourhood, filled with corrugated steel shacks, workers’ quarters from the Apartheid era and dirt roads.

Residents generally had electricity and running water, but their homes definitely left them open to the elements of dust, cold winter nights and stifeling hot summer days. The children greeted Erika and I warmly and hung onto our hands for the entire tour of their village. Accustomed to visits by tourists, they peppered us with questions about where we came from and what sports we liked to play. At the end of our tour we purchased some oranges from a local merchant and distributed them to the kids.

The next stop was probably the most famous church in South Africa. Regina Mundi is the Catholic church at the centre of Soweto that served to be the spiritual headquarters of the struggle against apartheid. Regardless of religious affiliation, Regina Mundi was the site where many of the local protesters who died in the struggle had their funerals. It also became politically significant as leaders in the anti-apartheid movement would meet here. It would eventually become known as the “Soweto Parliament”.

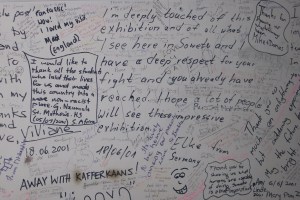

While the church has no significance architecturally (vintage 1950s or 1960s style) walking into this place sends chills down one’s spine as though one were entering Notre Dame in Paris. I think Regina Mundi has as much history as Notre Dame except that it is crammed into 50 years instead of 900. Inside, one finds scars of police raids in the 1980s when white police officers stormed the church and fired shots into the ceilings and walls. Our guide lifted the linen off the altar to reveal a large chunk of missing marble – the result of an angry police officer who struck the altar with his billy club. Upstairs, where one would normally find a choir loft, was a remarkable photo gallery of a famous South African photographer who chronicled the history of the struggle over a 50-year period with his camera. We were fascinated by these photos, so much so that our guide Mandy had to come and find us and drag us out because we were dawdling too much.

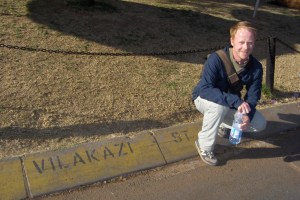

As we were leaving the church, Mandy informed us that because we had lallygagged so much we would only have 30 minutes to spend in the museum, our next stop on our trip, and that we would not be able to see Mandela’s or Tutu’s houses. Erika and I proposed to her that she drop us off at the museum and that we would spend the afternoon strolling through the neighbourhood to visit the Mandela and Tutu residences on our own. We had been told that Jo’burg is a dangerous city, but we calculated that we were fine to wander in the vicinity of the museum during the day. Strangely enough, no one had ever asked Mandy to do this before and she complimented us on our sense of adventure. We arranged for Mandy to pick us up later that afternoon at a predetermined location.

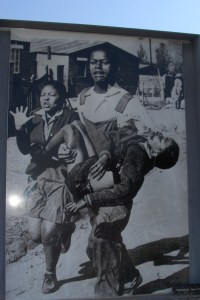

We began at the Hector Peterson Museum, named in comemmoration of a 13-year-old boy who was shot and killed by police during the famous Soweto uprisings of 1976.

The museum is small but excellent. It focuses on Soweto’s role in the anti-apartheid movement particularly the pivotal role the killing of Hector had on the psyche of the white minority in South Africa. The murder of dozens of black school kids in 1976 at the hands of the police and military led average white citizens in South Africa to finally question the apartheid regime they were supporting. For the next 15 years, the government fought a losing battle against the non-white majority, could no longer count on the unquestioning devotion of the white minority and began to face questions from the international community.

We left the museum and wandered around the neighbourhood toward the Mandela house. Instead of being greeted by muggers and gangs (as some white South Africans we later encountered would tell us ALWAYS happens in South African cities to white people!) we were greeted by friendly locals. Sure we were the only tourists walking around, but I never felt insecure for a moment. Instead we had homeowners call out to us from their doorsteps to ask us how we were and children running up to us to sing us songs.

The Mandela house was surprisingly small. He and his wife Winnie have not lived there for years. In fact the last time he lived there was in 1962, just before being sent to prison. The 4-room house today is a small museum to South Africa’s greatest leader, a remarkably humble place for a person of such stature. The inside of the place is festooned with plaques, photos, honourary degrees and other gifts he received before and after his exile to Robben Island.

Two of the plaques I found interesting were from the Ontario Teachers’ Federation and a Toronto Khalsa (Sikh) organization! Seeing “Ontario” and “Toronto” things on the other side of the world, I felt a strange sense of “what am I doing here?” I also began to think how privileged I was to have had the chance opportunity to shake hands with Nelson Mandela 6 years ago and now here I was standing in his house.

Well, that ends my travel journal. This has been as much an opportunity to document my ramblings and stray thoughts of an unforgettable trip as it has been a chance to share with all of you my experiences in a part of the world we could all stand to know more about. If I learned anything on this trip it is that despite the perceptions of sub-Saharan Africa as a desperate and hopeless place of hunger, drought and disease, there is a lot of hope and promise there too. Surrounded by the comforts to which we often feel so entitled in the protective cocoon of the developed world, I think we lose sight of our relationships with our environment and with each other. In Lesotho there are no homeless people because everyone has someone to look out for them; yet a country as wealthy as Canada has people freezing to death in the streets for want of place to live. This isn’t a question of resources, but a question of attitude.

People have been asking me what I accomplished as a Habitat volunteer. Reliable and affordable housing is a basic need and is even more important in a society where many parents are dying and leaving broken families unable to support themselves. But with a little outside help, the survivors are able to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table. The local Habitat affiliate in Lesotho was founded by six enterprising local women who have decided to work outside a typically male-chauvenistic society to find their own solutions to their struggle against poverty. In this situation people can take a little encouragement and make it go a long way.

I may find it hard to put into words what we accomplished, but the villagers we worked with have no problem at all. They are grateful for our help. An entire village in Lesotho knows they have friends in Canada and United States who helped them get on their feet. For each one of the 14 volunteers who went to Lesotho there are dozens more of their friends and family members back home who helped them get there through financial donations or moral support. The people of Khubelu village in Lesotho know this and for that they are grateful. And for that I thank you.

One response to “Fin”

Hello Andi, what a nice travel note that you have shared here! I have been doing research on visitors’ reactions to the small photography exhibit at Regina Mundi Church and also came across yours’ 🙂 I would like to use one of your photos in a written piece. Would be great if you can get in touch! keep on sharing your thoughts! F.